ADDIE Explained: Analysis

By: James Nichols, Sharon Walsh and Muhammed Yaylaci

Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Describe the definition of analysis and where it fits in the ADDIE model.

- Describe the how, what, when, where, why, and how of analysis questions are answered.

- Describe the theoretical framework underpinning analysis.

- Define and describe the different types of analysis including: goal, learner, needs, and environment.

- Describe the necessary steps in the analysis phase.

- Implement the analysis steps in a given situation.

Introduction

Analysis is the first stage in the ADDIE model because one must first determine what must be done in order to know what needs to be accomplished. In Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, the Cheshire Cat remarks to Alice it doesn’t matter which way you go if you don’t care where you will end. The same is true in developing instructional materials and curriculum; if one does not care about the final result (an odd choice indeed), analysis would not matter because there are no requirements to compare the result. The analysis stage focuses on WHAT tasks should be accomplished for WHOM (i.e. learners) and HOW these learners will accomplish the tasks by specifying WHERE (i.e. the environment) they need to be able to perform the tasks. The Analysis stage provides this gathered information to the remaining stages of the instructional design process, which builds upon this critical information to produce the solution. This chapter will discuss who is involved in the process, the different types of analysis such as goal analysis, learner analysis and task analysis as well as how to conduct a needs assessment.

The critical questions to be answered in the Analysis stage are the who, what, when, where, why and how questions as seen in Table 1. The WHO is important to know the characteristics of the people (i.e. the learners) who will be using the instructional materials by conducting Learner Analysis. The WHAT is important for formulating the desired result or outcome of the instruction by tasks as described in Goal Assessment. WHEN determines the amount of time available for crafting a solution as well as the amount of time available for the learners to proceed through the material and as such is not discussed further in this chapter. WHERE is the context or environment the learners will need to be able to perform the tasks (i.e. WHAT). WHY attempts to determine the need(s) for the instruction due to a lack of performance or understanding exhibited by the learners through conducting a Needs Assessment. HOW refers to the specifics of accomplishing the goals in the WHAT questions by conducting a Task Analysis.

Each of these questions assist in understanding the instructional problem to be solved and includes certain freedoms and constraints making each a unique problem to solve. For example, designing instruction for a hospital will likely be influenced by HIPAA and other government standards specific to healthcare while designing for the military will likely focus more heavily on security. Thus, the culmination of the answers to these questions will result in a path to a distinctive solution, which may not always lead to instructional training. Note as the instructional designer, you may or may not need to conduct all of these analyses as some of them may have already been done for you and some may not be relevant depending upon your circumstances.

Table 1. Critical questions in analysis.

| Critical Questions | Answers |

| Who | Know the characteristics of the people (i.e. the learners) who will be using the instructional materials by conducting Learner Analysis |

| What | Formulating the desired result or outcome of the instruction by tasks as described in Goal Assessment. |

| When | Determines the amount of time available for crafting a solution as well as the amount of time available for the learners to proceed through the material and as such is not discussed further in this chapter |

| Where | The context or environment the learners will need to be able to perform the tasks (i.e. WHAT). |

| Why | Attempts to determine the need(s) for the instruction due to a lack of performance or understanding exhibited by the learners through conducting a Needs Assessment. |

| How | The specifics of accomplishing the goals in the WHAT questions by conducting a Task Analysis. |

Based upon the answers to the critical questions of who, what, when, where, why and how, a better solution to spend less time, money and resources while still being effective, may be through creating a handout or instructional guide rather than on training. For example, suppose workers at a fast food restaurant have difficulty knowing the proper layers for each of the burgers. Rather than spend additional effort and money trying to train the workers, the workers may only need a handout or guide posted above where they work to assist in jogging their memory. Since the workers may not be working each day, trying to remember the specifics of the layers through additional training is not likely to be as effective as providing an instructional guide. An example in Gagne, Wager, Golas and Keller (2005) is from school safety data not seeming reliable and thus it was believed to be the data-entry operators fault. However, the solution was found in the lack of consistency in defining safety violations as well as the politics of schools not submitting as many reports to be rewarded and not reprimanded. In this case training would not have corrected the problem and would only aggravate the data-entry operators. It is critical to be able to determine whether an instructional guide or resolving another issue is preferable to training so the problem is solved.

Determine Instructional Problem (i.e. requirements)

Once it has been determined the need is an instructional issue and not the result of poor technology, policy/procedures or environment, the instructional designer can proceed with instruction. But how or when should someone determine if the problem is an instructional problem? According to Rossett (1999), there are four instances to automatically check for a performance issue. The four cases are: 1) existing performance problems, 2) when what has been developed is new, 3) continuous development of employees for benefitting the company and 4) to provide information for planning for the future. Also, since this world is constantly changing, it is important to continue to revisit how the environment, learners and tasks have been changing throughout the process so the instructional solution is not extinct before it is implemented.

An example of an instructional problem is a situation in which workers in a factory are unprepared to work on the new equipment coming in six months because it is different from what they have worked on currently. An example of a problem for which the solution is not instruction is a situation where an employee of a college is entering student application data and needs to be completing 10 in an hour but only completes five due to other duties such as answering the phone or perhaps the ergonomics of their work environment. The employee doing data entry knows how to type and where to enter the data but there are other factors involved such that instruction will not show any performance improvement.

Desired status, actual status, and gap

A simple equation to determine if there is a need is broken down into three parts according to Dick, Carey and Carey (1978). The equation is:

Desired status is defined as the goal an organization is shooting to achieve. Actual status is the current performance or status of achieving the goal. Need is the difference between the desired status and the actual status or the bridge necessary to cross this gap. To illustrate this equation, suppose a college is wanting to ensure graduation of 90% of the students who enroll but only 75% are achieving graduation. The desired status is the 90% graduation of students who enroll with actual status being 75% so there is a gap of 15% between what is desired and the actual completion rate. Since there is a gap, there is a need to figure out what can be done to ensure 15% more of the enrolling population will graduate.

Who should be involved and what they do

After determining the instructional problem, now the question is who are the stakeholders or the people who should be involved in the process of developing the solution because they have valuable information and experience to contribute. Once the stakeholders are known, it is also important to define their roles. Below is a list of typical stakeholders who will be involved in most projects as well as information about brainstorming for other stakeholders and how each of the stakeholders should be involved.

Brainstorm about stakeholders

Determining who the stakeholders are is an important part of the analysis process as well as the overall ADDIE process as these are the people who inform the process and will have some determination in the success or failure of the process due to their experience and knowledge. Preferably the known stakeholders should convene to determine who else should be involved. As in any brainstorming process, it is best to allow ideas to flow freely and write down every possible stakeholder without providing criticisms as to whether it is a beneficial stakeholder (i.e. stakeholder is hard to work with, won’t provide valuable information, is lazy, etc). Note even those who may be negatively impacted should be considered a stakeholder even if they will not be involved in the process because this can affect the future solution. For example, in developing a computer system, a hacker would be considered a stakeholder since how well the system’s security is designed affects the hacker’s job. Though we may not want a hacker to be involved in the development process, it is important to keep them in mind so we can develop a robust system. Similarly, it is important to consider all stakeholders and their involvement as the politics of someone being left out who feels they should be involved, could jeopardize the success of the instruction.

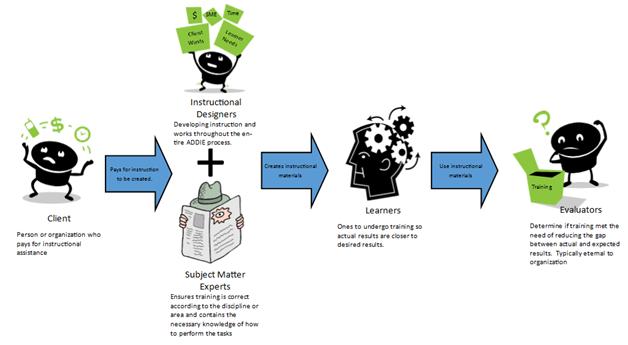

After the list is drafted, it is important to determine if any additional stakeholders should be invited to be involved and what role they will play in the process. Some individuals may have multiple roles to play, especially in a smaller organization. The following list is a starting point to the stakeholders who should be involved as well as their roles in the process and Figure 1 shows how the main stakeholders interact:

Instructional Designers are involved in developing the instruction and will be involved in the entire ADDIE process by eliciting requirements of what the instruction must do, to designing and developing the instruction as well as the implementation of the instruction.

Client is the person or organization who pays for the instructional assistance. This person or organization may or may not have been the one who saw the need for solving the instructional problem but they will determine if the solution is acceptable and will need to agree and sign off on all decisions as they are paying the bill.

Discoverer is the person who saw the gap in actual results versus desired results and took steps to determine how to reduce the gap. This person is likely to be involved in the entire process and may be the same as the client or may be the client’s proxy.

Learners are the people whose actual results should be closer to desired results. These are the workers in the organization who will undergo the training to improve on their tasks. It is not always possible to talk with the learners nor test the training on the learners so it may be necessary to have a proxy learner who is someone very familiar with the tasks the learners perform.

Evaluators are typically people external to the organization who will determine if the training met the need of reducing the gap between actual and expected results. It may be important for them to be involved early in the process to be able to start to determine how the instructional solution will be evaluated and can provide suggestions on changes to the solution before it is too late.

Supervisor is the boss of the learners who may have insight in other reasons as to why their workers may be underperforming or their workers have a lack of understanding. Supervisors will be impacted by the amount of time the learners will spend on training as well as have insight into the prerequisites the learners have in addition to their typical background. Supervisors may not be involved in the process but may be a possible proxy for the learners.

Subject-Matter-Expert is the one who ensures the training is correct according to the discipline or area because they are highly skilled and contain the necessary knowledge of how to perform the tasks. The Subject-Matter-Expert should be involved in all phases to determine the correctness of the material contained in the instruction.

Figure 1. Instructional design stakeholders and process.

Now knowing who the stakeholders are in the process, it is important to identify what the goals of the instruction will be through goals analysis.

Analysis Checkpoint

Goals Analysis

Goal analysis is the technique used to identify the instructional goal and determine the necessary steps an learner must take to achieve the goal. While instructional designers try to find what they need to do/accomplish/solve, they accept there is a problem has to be solved or a need to be achieved in goal analysis. In the goal analysis part, instructional designers try to create meaningful goals directly addressing solutions or needs. As in many aspects of social sciences, there are several methods to conduct a goal analysis.

The first goal analysis method is to work together as a team. According to Morrison, Ross, Kalman and Kemp (2011) there are seven subtopics ID professionals should follow for a successful team goal analysis: identifying the aim, setting goals, refining goals, ranking goals, re-refining goals and the final ranking of the goals.

In this scenario, an instructional designer is tasked with creating a fall protection lesson for a roofing company using OSHA guidelines. The designer first conducts a goals analysis:

Table 1. Step, definition, and scenario for goal analysis.

| Step | Defined | Scenario Example |

| Identify Aim | Identify one or more aims or general ideas of what learners need to know. | At the end of the training, the learner would be able to: explain and perform basic roofing fall protection skills as found in the OSHA guidelines. |

| Set Goals | The team brainstorm goals for each of the aims which should describe learner performance behaviors at the end of training. | At the end of training, the learner will be able to set up a controlled access zone including: *the nature of fall hazards *The role of each employee in safety monitoring systems *setting up appropriate barriers *The correct procedures for the storage and handling of fall protection equipment *The limitations of mechanical equipment in low-sloped roofs *determine when and how to use safety net systems *create personal fall arrest systems |

| Refine Goals | The team refines and clarify the goals by combining similar goals and eliminating any duplicate goals. | *the nature of fall hazards *barriers: setting up, storage and handling, and limitations *safety nets *role of each employee *personal fall arrest systems |

| Rank Goals | The team ranks the goals to determine the most important ones to be taught. | *the nature of fall hazards *role of each employee *personal fall arrest systems *barriers: setting up, storage and handling, and limitations *safety nets |

| Re-refine Goals | Refine the goals again by identifying discrepancies between current performance and the proposed goals. | This roofing company has a team that set up, removes, and stores the barriers. At this point, the company needs individual training of personal fall arrest systems including the role of each employee in fall protection |

| Final Ranking | Determine the final ranking of the goals and determine how vital each one is to the final training. | This lesson is only about the personal fall arrest system. |

Another method of goal analysis is for the instructional designer to analyze the goal without a team. In this case, the designer is looking at the goal and identifying the domain of the as either psychomotor (i.e. physical), intellectual (cognitive), or verbal information skill? The type of domain will influence the next steps necessary in goal analysis. If the skill is psychomotor or intellectual the designer creates a flowchart to subdivide each step of the goal down into at least five steps but no more than fifteen per one to two hours of instruction. The flowchart allows the designer to specifically see the necessary physical (psychomotor domain) or cognitive (intellectual) steps the learner must complete to successfully complete the task. A sample flow chart is provided in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2. Example linear flowchart process.

If there are decisions to be made, a flowchart similar to Figure 3 to include a diamond representing the decision, would be more appropriate.

Figure 3. Example flowchart process with branching.

If the domain is verbal information, then the designer plans the question and answer sequence within an outline. In the above roof safety example, roofing safety is psychomotor and, since the goal is to limit the steps down to around five to fifteen per hour or two of instruction, this session would also concentrate on personal fall arrest systems.

For all domains (psychomotor, intellectual, and verbal) the flow charts are a physical representation of the necessary steps and allow the designer to clearly visualize how to instruct the learner to master the goal.

Learner Analysis

Learner analysis is the systematic determination of relevant attributes of the learners to the overall training goals. The relevant attributes depends entirely on the organization and the ultimate training goals.

When conducting a learner analysis, the first step is to look at the learners themselves. For example, some general characteristics influencing training requirements are: gender (single-gender or mixed gender course), age (single age group or mixed age group), work experience (all new roofers or new and experienced roofers), and levels of education. This can be done either by survey or a site visit with structured interviews.

Beyond the general characteristics of learners, designers should know what prerequisite skills the learner should already have before attempting the course. This includes previous work experience as well as educational levels (Morrison, Ross, Kalman, Kemp, 2011, Dick, Carey, & Carey, 2005). It is also important to know the attitudes each learner is bringing into the course. Beyond the basic knowledge and skills to get started, knowing what type of previous experience the learner has had with this material is important in determining their attitude and motivation. Will he or she come in with an open mind or resistant to the training? Is he or she motivated to learn or is there little interest in the topic? (Morrison, Ross, Kalman, Kemp, 2011; Dick, Carey, & Carey, 2005).

Along with pre-requisite skills is a need to understand learners with disabilities. While a knowledge of the population of the learners’ academic levels is important, the why behind their academic levels is equally important.

Learning styles allude to the notion people learn in different methods. Some prefer reading, others listening, while others prefer doing. Targeting learning style preferences might aid small group learners in tackling the material (Morrison, Ross, Kalman, Kemp, 2011).

Another consideration for designers in this global society is diversity. As designers set up the course, a major consideration is whether English is the dominant language of the group. How should the trainer work with learners without strong English skills? A goal for designers is to develop language and literacy across the curriculum, which allows learners to make meaning within real-world contexts while learning through conversation (Morrison, Ross, Kalman, Kemp, 2011). An example of the results of a basic learner analysis would look something like the following for a commercial/industrial roofing company:

Table 2. Information categories, data sources, and learner characteristics.

| Information Categories | Data Sources | Learner Characteristics |

| Entry behaviors | Interviews: Foremen, human resource manager | Learners have adequate physical skills to begin instructions. |

| Prior fall protection knowledge | Interviews: Foremen, human resource manager | Limited roofing experience, including lack of fall protection training. |

| Attitudes toward fall protection | Interviews: Target learners, current roofers | The current roofers are aware of the need for fall protection even though they complain about how the harnesses infringe on freedom of movement. The targeted learners are unaware of the need for the equipment. |

| Attitudes toward potential delivery system | Interviews: Target learners, current roofers, human resource manager | Learners preferred a hands-on demonstration type program. |

| Motivation for instruction | Interviews: Target learners, current roofers, human resource manager | Learners are motivated by the need for a job and are willing to do the training for pay. |

| Educational and ability levels | Interviews: Target learners, current roofers, human resource manager | Education: Learners typically have a high school diploma or the general equivalent.

Ability: Learners may have roofing experience but are novices in fall protection. |

| General learning preferences | Interviews: Target learners with preference quiz | 100% of the new roofers prefer hands-on learning to reading or watching. |

| Attitudes toward training organization | Interviews: Target learners | Learners have no prior experiences with roofing company but do have prior educational experiences. Attitudes are mostly ambivalent with a “wait and see” attitude. |

| General group characteristics | Interviews: Target learners, current roofers, human resource manager | Interviews: Target learners, current roofers, human resource manager |

Needs Assessment

A needs assessment determines if there is a discrepancy between what the participants should be doing and what they are currently doing. Burton and Merrill (1991) classify the types of needs into six categories: normative needs, comparative needs, felt needs, expressed needs, future needs and critical incident needs. An instructional designer should use these categories to peruse what may be true for their situation.

i) Normative Needs

Normative needs compares an identified group to a national standard such as national exams. The Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) or Graduate Record Exam (GRE) are examples of normative assessments. Some normative needs exist for safety reasons such as company safety records or service such as an airline’s on-time rating. A normative need exists when the target population is below the established norm. For example, if a high school’s Algebra End of Course Exam (EOC) pass rate is below the state and the county, then there is a defined normative need. Normative needs assessments are conducted by analyzing the normative data.

ii) Comparative Needs

Even though, comparative needs look similar to normative needs, they have one significant difference separating them. Instead of a commonly accepted standard, such as national standards, the learning group is compared with another group to reach their achievements and abilities on the topic (Morrison, Ross, Kalman, Kemp, 2011). For example, a company hires an instructional designer to create a program for their new recruits to learn as much knowledge as their senior workers about their machines. So the knowledge and skill difference between senior employees and new recruits will represent comparative needs. A designer conducts a comparative needs assessment by first determining area for comparison and then identify a comparative audience to collect and compare the data.

iii) Felt Needs

Felt needs are based on learners’ necessities and wishes to improve. Felt needs represent a perceived gap between a desired performance or skill level and the current performance or skill level. For example, if a teacher notices her secondary science students are not reading on grade level and she does not have the skills to improve their reading while teaching science, she has a felt need. If she acts on that need and takes classes in content area reading, then she has moved to expressed needs.

iv) Expressed Needs

Expressed needs is an individual taking action on felt needs. Both felt and expressed needs are identified through interviews.

v) Future Needs

Future Needs is based on growth and development in every aspect of human lives, everything changes day by day. With calculations and inferences about current situations, it is very hard to anticipate the future so this is by far the most difficult of the needs categories to achieve. So according to these anticipations, an instructional design program can be created for preparing future learners for upcoming situations. For example, a computer engineering program in a university teaches its students the Visual Basic programming language. While they are teaching Visual Basic, another program, known as Java, starts to dominate the marketplace. Since the speed of the change in computer related topics is so fast, it is easy to understand students will need to know Java after a couple years from present day. Therefore, it is logical to teach students the Java programming language to prepare them.

vi) Critical Incident Needs

Critical incident needs are likely to be the focus when there is a major failure in the system such as a chemical spill, medical treatment error, fall, etc. Critical incident needs are identified during what-if planning situations.

Conducting a needs assessment involves four phases: planning, collecting and then analyzing data, and the final report preparation. Planning is the basis for an effect needs assessment. Since an effective needs assessment focuses on just one target audience, the first step is to identify and define the targeted learning audience. This step is vital since not all data types are necessary for all learning audiences. For example, national normative data might not be needed for a software change or a new training program. The second part of planning involves determining the stakeholders involved in the study. For example: supervisors and managers are important to business while parents, teachers, and administrators are important to the school setting. Step two is collecting the data from the stakeholders. In an ideal world, all stakeholders are involved in the study. However, if the group is large or geographically diverse, it might not be economically or even logically feasible to include everyone. However, it is important to include samples from representative sites and regions that represent the target population as closely as possible. Data analysis shows the needs priorities of the group. The needs might be prioritized by economics, impact on the organization, or even timeliness. The final report presents a summary of the study’s purpose and the process used to compete the study, along with a results summary and the necessary recommendations based on the data.

Analysis Check Point

Context Analysis

Context analysis is determining the context or settings in which the learner will use the skills and knowledge learned is another piece of the analysis puzzle since the goal of learning is for the learner to transfer the knowledge beyond the classroom. A designer should observe the environment in which the learner is expected to perform the skills or present the knowledge learned. There are three major types of context: orienting, instructional, and transfer.

i) Orienting Context

Orienting context introduces the instructional program by providing the experiences in which the new information will based. It is designed to motivate learners by establishing a need for learning the new information of building a bridge between prior knowledge and the new knowledge.

Orienting context goes back to learner analysis. What skills, attitudes, knowledge, and motivation is the learner bringing to the course? The answers to the question determine the design of the instruction (Morrison, Ross, Kalman, Kemp, 2011).

Orienting context contains three main parts. first, instructional designers should analyze students’ attitude and motivations based on the data gathered in learner analysis (Morrison, Ross, Kalman, Kemp, 2011). This process gives a clear look to instructional designers the learners’ interest and ideas on the course. Secondly, learners’ expectations and goals of the course should be compared. If a program cannot convince learners the importance of the course, the gains achieved will be minimal, if any at all. For the final step, if there is a concrete achievement such as degree, learners are more likely to follow their learning processes. So it is important to put a prize at the end of the course, as well as clearly conveying the benefits of taking the program.

ii) Instructional Context

If an instructional designer wants his program to succeed, he has to analyze and calculate every aspect of the learning experiences, delivery methods, teaching techniques, etc. While learning experiences should be carefully analyzed and organized, delivery methods also have to be chosen based on their compatibility with content and facilities the program has already or will soon have. For example, even if the designer created an HD video to teach learners the phases of cell division, it will be useless if the school only has a 30-year-old TV and no intention of purchasing a new one.

Another important detail instructional designers should take into account is scheduling of the course. It will be difficult to teach eighth-grade learners algebra in the summer time while their friends play video games and swim all day.

Instructional context includes environmental factors for instruction. A few key questions about the facility include:

• What type of technology is available for the presenters?

• What type of technology is available for the learners?

• How noisy is it?

• Will the lighting and temperature be conducive for type of instruction?

• What is the seating arrangement?

• When and where is the course scheduled (Morrison, Ross, Kalman, Kemp, 2011)?

Since the ultimate goal is transfer of skills beyond the classroom, the transfer context is a vital piece of instruction. What type of follow-up support will the learner have in transferring the knowledge beyond the classroom? Will the learner have an opportunity to practice the skills or demonstrate the knowledge in a timely fashion?

iii) Transfer Context

When creating an instructional design program, it is crucial to transfer knowledge and skills learners learnt from the program to real life as defined as transfer context. Ideally, instruction will be provided at the time of need and in the location the new knowledge or skills will be used. However, the location used is not necessarily the easiest method for instructors. In our roofing example, the ideal training takes place at both the office and the worksite. At the office, the instructor would go over each piece of a proper safety harness and then she would then show the learners worn out parts on another harness and as a team the learners would replace the worn parts. The final task in the office is to analyze several harnesses for wear and individually replace parts until every harness is ready for use. She would then show the learners how to properly wear the harness. On the worksite ground, the team would again inspect the harnesses and properly place the harness on their bodies. On the roof, the instructor would show them how to attach their harness to the system and confirm the learner can easily and correctly attach and detach their personal harness from the fall protection system.

e) Task Analysis

Using the information gained about the learners and the purpose of the instruction, now it is time to determine what tasks the learners will need to be able to perform. Task Analysis seeks to elicit the required information from the SME in order to understand the procedures, content, methods, etc to be conveyed to the learner.

i) Topic Analysis

As it easily understandable from its name, topic analysis focuses on the topic the instructional design program is going to cover. It should be approached like writing an essay. As a first step, the designer gathers general data about the topic and tries to understand the boundaries of the topic as done in writing an essay by first providing an outline with the high-level details (such as the numbers on the first level of the outline). After gathering information, now it is time to go deep into the details about the topic to understand its far aspects, relationships, and characteristics (i.e. by providing secondary bullet points in the outline for the essay). And finally, the gathered data is ready to be organized for decisions and processed in the remaining phases of the instructional design process (i.e. the topics in the English paper outline may be rearranged in a more logical structure by combining or subdividing topics or through reordering). In addition, two things should always be remembered when creating an instructional design plan: what really needs to be taught and the structure of the topic.

ii) Content Analysis

In the content analysis, designers seek data about facts, concepts, rules, and procedures of the content, along with the interpersonal skills and attitudes of both learners and teachers. The data of skill and attitude can be collected with questionnaires, surveys, and especially with observations. Students’ reaction to similar topics can be also useful for data collection. For example, students’ positive attitude and high level thinking capabilities of functions in mathematics can be followed in trigonometric functions. Therefore, this data can be extremely helpful for ID professionals when creating and organizing learning experiences for the program

iii) Procedural Analysis

In the step of procedural analysis, instructional designers gather information about sequences, priorities, etc. about learning experiences or the topic the program is about to teach (Morrison, Ross, Kalman, Kemp, 2011). Procedural analysis helps instructional designers to understand relationships among the elements of the topic. This step is one of the most important steps of the whole design process because all design process and learning experiences will be based on the procedure list and the data gathered. For example, an instructional designer hired to create a program on troubleshooting computers would create a procedure list that includes checking to ensure the power cable of the computer is plugged into both the wall outlet and the computer as the first step since this is typically true. Some learners may not understand the situation and need help if an unplugged computer does not work even though there is nothing wrong with the computer. But it is not possible to know the computer does not work unless it is plugged into the wall outlet and has been turned on to be used. It is most important to start out with the basics and work toward more complex problems.

Task analysis can be done in many different ways depending on the circumstances. The goal of the task analysis is to break the main topic down into manageable chunks for instruction. One method is to create an outline starting with the topic of training including the six structures of task analysis: key facts and concepts, principles and rules, procedures, interpersonal skills, and attitudes (Morrison, Ross, Kalman, Kemp, 2011).

Designers then look at the facts to be taught including the vocabulary and key concepts of the task. In our roofing example, key vocabulary includes: personal fall arrest system, arresting force, maximum deceleration distance, snap hooks, horizontal and vertical lifelines. Key concepts are categories used to group related ideas. For example, personal fall arrest system includes the body harness, lifelines, ropes and straps, and anchorages.

Principles and rules describe relationships within concepts. Procedures describe specific orders or sequences a learner must do to implement the training. In this case the body harness is put on the body before connecting it to the lifeline. Other key concepts include verbal and nonverbal interpersonal skills and attitudes of the learner.

Another method of task analysis is to break down each learning goal to the basic steps necessary to complete the goal. Once again, there are multiple methods to create a procedural task analysis. One method is to simply walk through the observable steps with an SME. During the observation, the designer asks key questions:

• What physical or mental actions must a learner do to complete the task?

• What knowledge does the learner need to complete the task?

• What cues inform the learner of errors along the way?

The designer then takes the key answers to these key questions and creates either a table or a flowchart such as was completed during learner analysis.

Procedural task analysis does have limitations since it focuses exclusively on subject-matter-experts and observable tasks. However, many tasks involve complicated cognitive components. Thus adding cognitive tasks analysis to procedural task analysis greatly enhances the task analysis. One method of cognitive task analysis is goals, operators, methods, and selection (GOMS) as discussed by Card, Moran and Newell (1983). This method focuses on adding goals of why the task is important to the learning outcome. Another cognitive task analysis is the applied cognitive task analysis process (ACTA) which asks the subject-matter-expert to identify three to six broad tasks that must be performed to complete the goal. The SME and the designer then determine the knowledge necessary to complete the task and ultimately the goal while simultaneously looking for errors novices may make in the process (Morrison, Ross, Kalman, Kemp, 2011).

[sta_anchor id=”closing” /]

Closing Remarks

As discussed in the chapter, the purpose of the Analysis phase is to determine if there is an instructional problem to solve or whether the issue is through some other means of organizing or clarification. If there is an instructional problem to solve, it is collecting the characteristics of the learners through Learner Analysis, the reasoning of the instruction through Needs Analysis, the aim through Goal Assessment and the steps to achieve the goal(s) through Task analysis. The goal of the analysis phase is to present the findings to the stakeholders and clearly determine whether developing instruction should be pursued. This “Go or No Go” decision is similar to Volere’s Project Blastoff in the realm of software engineering’s requirements phase in the Software Development Life Cycle. Volere’s Project Blastoff determines the scope of the project, the stakeholders involved and an analysis of the problem (Robertson & Robertson, 2012). At its conclusion, a decision is made to proceed or not proceed to complete the scope of the project determined. This same idea of determining the scope of the project, who is involved, and whether this is an instructional project and should continue is important in the ADDIE model as well. The next phase in the ADDIE model is Design and there is no reason to Design if you are not designing for an instructional problem.

Each of the discoveries made from the Analysis phase should be documented for the Design phase. The Design phase will use the information gleaned to create an effective instruction based upon where the learners are currently at in their performance and perceived understanding, in the context or environment they are to perform based upon the needs, goals and tasks.

Analysis and Design is a fuzzy boundary. It is important to be careful about prescribing too much during analysis. The focus is to determine WHAT needs to be done as Design will determine HOW it should be done. However, if there are constraints to how something should be done, that should be included as a requirement. For example, if the learning management system (LMS) being used by the school is Canvas, then a constraint to constructing course materials may be using Canvas as the delivery system instead of paying for a completely new system. Then the design is constrained by the requirement found during the Analysis of the situation.

Chapter Summary

Analysis phase is critical to the entire instructional design process for all of the other phases depend upon the discovery of information during the analysis phase. To determine if an instructional solution is necessary, first determine the desired status of the performance people should be operating and see if there is a gap between the desired status and their current performance level or actual status.

The people to involve in the process include the instructional designer, client, subject-matter expert, learners or their proxies as well as those who will evaluate the instruction. The one who discovered the need as well as supervisors of the learners may also be included in the process. Goal analysis focuses on determining the components of a solution to the instructional problem through the seven steps of identifying the aim, setting goals, refining goals, ranking goals, re-refining goals and the final ranking of the goals.

Learner analysis focuses on the characteristics of the learners, which means reviewing their backgrounds, learning styles, prerequisite knowledge, personal and social characteristics, disabilities and cultures all influence their view of instructional materials.Conducting a needs assessment assists in determining the reason(s) for the gap. The deficiency could be due to: normative needs, comparative needs, felt needs, expressed needs, future needs and critical incident needs. Consideration of the environment is important in designing the instruction as well as the tasks the learner will need to perform.

Discussions

- Based on your readings, should analysis be approached from a behaviorist, cognitivist or constructivist point of view? Why?

- Is it acceptable to determine an instructional intervention is not necessary? Why/Why not?

- Why is it important to conduct a learners’ analysis?

- Why is it important to conduct a needs’ assessment? Do you think this is done in the real world? Why/Why not?

- Explain how the environment can change the instructional design.

- Suppose you are designing instruction for construction workers. Who would be the stakeholders involved? What would each of their roles be? What kind of information would you want from each of them?

- Discuss the felt needs and expressed needs. What are the main differences and similarities between them? Why is distinguishing them is so important?

- What are the main principles of procedural analysis? Why is it so important for organizing learning experiences and activities?

Analysis Practice Assessment

The end-of-chapter practice assessment retrieves 10-items from a database and scores the quiz with response correctness provided to the learner. You should score above 80% on the quiz or consider re-reading some of the materials from this chapter. This quiz is not time-limited; however, it will record your time to complete. The scores are stored on the website and a learner can optionally submit their scores to the leaderboard. You can take the quiz as many times as you want.

Assignment Exercises

1. Copy and fill in the chart in the table below. For each analysis, explain its purpose, stakeholder’s involved, best ways to conduct the analysis. Make sure to take notes on how you will utilize this information in your career.

| Purposes | Stakeholders | Best Ways to Conduct | Notes | |

| Goal Analysis | ||||

| Learner Analysis | ||||

| Needs Assessment | ||||

| Environment/Content Analysis | ||||

| Task Analysis |

2.Think about the differences between educational and non-educational instructional design examples. How can application and principles vary/change between these two areas? Which things instructional designers have to take into account for a successful instructional design for different areas? Please provide a one-page detailed explanation of this question, and add citations, if applicable.

3.Discuss the capability of each type of analysis on preventing future problems in the instructional design progress (design, development, etc.). In what way(s) are they unable to assist in preventing future problems? Give at least one scenario demonstrating how they are unable to assist in preventing future problems.

4.Conduct a learner analysis for your classmates. Try to analyze at least five of your classmates with either online or face-to-face tools. Us questionnaires, polls, and interviews to assist in understanding your classmates. Try to fully address at least three main characteristics about your classmates, which would impact an instructional design if they were the students.

5. Describe several scenarios where the goals for different stakeholders would conflict. What are some solutions to resolving conflicting goals for different stakeholders? What should be done if conflicts are unable to be resolved.

Group Assignment

Given: A scenario by your instructor, what information is needed to conduct each of the following analyses?

A. Goal Analysis.

B. Learner Analysis

C. Environmental Analysis

D. Context Analysis

E. Task Analysis

Then: Discuss the capability of each type of analysis on preventing future problems in the instructional design progress (design, development, etc.). In what way(s) are they unable to assist in preventing future problems? Give at least one scenario demonstrating how they are unable to assist in preventing future problems.

[sta_anchor id=”reference” /]

References

Burton, J. K., & Merrill, P. F. (1991). Needs assessment: Goals, needs and priorities. In L. J. Briggs, K. L. Gustafson, & M. H. Tillman (Eds.), Instructional design: Principles and applications (2nd ed., pp 17-43). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Card, S. T., Moran, T. P., & Newell, A. (1983). The psychology of human-computer interaction. Hillsdale,. NJ: Erlbaum.

Gagne, R. M., Wager, W. W., Golas, K. C., & Keller, J. M. (2005). Principles of Instructional Design (5th ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Robertson, S., & Robertson, J. (2012). Mastering the Requirements Process: Getting Requirements Right (3rd ed.). Westford, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley.

Rossett, A. (1999). Analysis for human performance technology. In H. D. Stolovitch, & E. J. Keeps (Eds.), Handbook of performance technology: Improving individual and organizational performance worldwide (pp. 139-162). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

Morrison, G. R., Ross, S. M., Kemp, J. E., & Kalman, H. (2012). Designing effective instruction (7th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley & Sons.